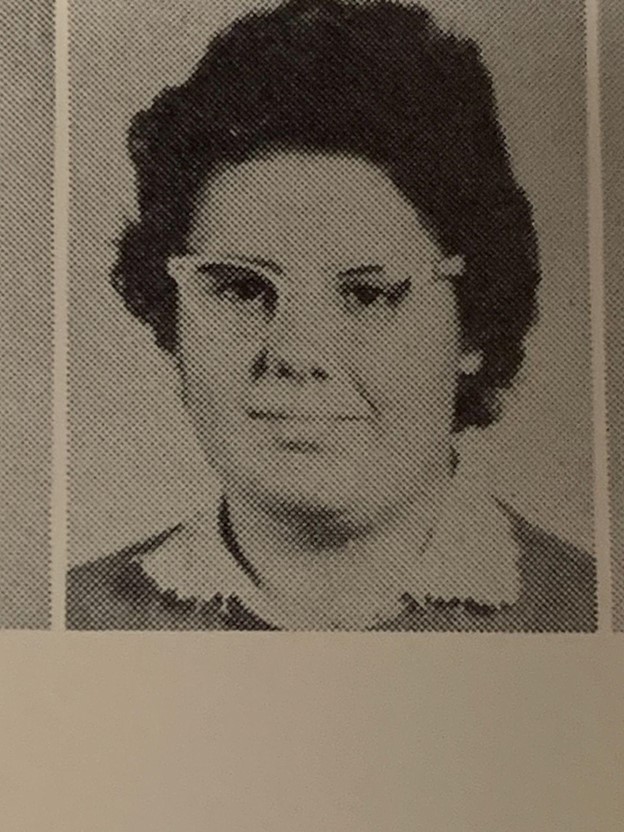

In the 1960s, Gertrude Evans was a young woman. Evans wanted to swim in the Leesburg Fireman’s swimming pool, but there was one problem: she was Black, and at the time, Loudoun County was refusing to desegregate. “As a child my friends and I were not allowed to swim in the Firemen’s swimming pool,” Evans said. “Although there was no White only sign, we knew our place. Some barriers we did not cross.” Even after protests, Evans and fellow protesters could not get the pool integrated. Later, a court order was brought on behalf of four Leesburg teens to open the pool to all. “In 1968 after refusing to integrate the Fireman’s pool was closed to everyone and filled in with garbage, dirt, and cement,” Evans told a room of students and faculty on January 18.

Loudoun County was resistant to desegregation, even after laws and policies were put in place. Loudoun County Public Schools was included, and it was one of the school systems that didn’t immediately integrate their schools after Brown vs. Board of Education. Former English teacher Arlene Lewis believes current students can benefit from learning history. “I think a lot of people don’t really understand the history,” Lewis said. “While Brown vs. The Board of Ed. was decided in 1954, Loudoun County Public Schools resists until 1968. Even when selected students were allowed to come to Loudoun County High School, they were still split up in classes,” Lewis said. It should be noted that this was the students’ own choice to be separated from one another.

“I don’t think a lot of people realize how Loudoun County really resisted, from 1954-1968, and how it was really reflective of what was going on in the nation. We tend to think of Brown vs. Board of Ed. and that was it. There were pockets of resistance even outside of education,” Lewis said.

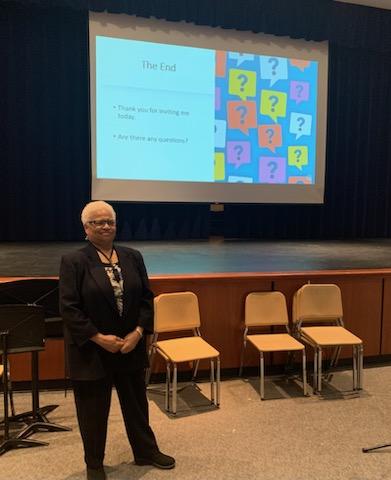

Lewis is a co-president of the Gamma Sigma chapter of Alpha Delta Kappa, which is an honorary organization for women educators. Lewis organized a presentation for January 18 here at the school about the integration of LCPS. She was able to invite local artist and historian for the Loudoun Douglass Alumni Association, Gertrude Evans, to speak at this event. According to Lewis, this is the first time Alpha Delta Kappa has sponsored a school presentation, though the organization participates in the Teacher Cadet Signing Ceremony each year. “When we decided to invite Ms. Evans to speak, we were thinking it would really be informative for the Teacher Cadets,” Lewis said.

The organization also sponsors the annual Women’s Summit. “I felt a women’s organization, such as ours, should be supporting young women generally, not just those who would like to teach,” Lewis said.

People invited to attend the meeting on January 18 included the Teacher Cadets, as well as Educators Rising students, students in the Black Student Union, and any students interested in local history.

During the meeting, Evans talked about her childhood experiences with segregation. Being an artist, throughout most of the presentation she showed many pieces of art she had created that visualized what she was talking about.

Evans is an alumna of the Douglass School, the only school for African American students until the end of segregation in LCPS in 1968. Evans explained the history of Douglass, noting that during the 1930s, African American parents pressed the school board for a new high school because the old high school off of Union Street was dilapidated and didn’t meet standards. “The Loudoun County School Board told our parents there was no money for a school, and they didn’t have the land,” Evans said. “The parents and the county-wide league raised funds to purchase the land, which they did. They purchased the land in secret, at night from a White man, Mr. Gibbons for $4,000, which is now equivalent to over $90,000. After that they still had struggles as far as getting the school built, but eventually their struggles ended and Douglass was built,” Evans said.

Evans later explained that the Douglass School was not as well-equipped compared to some of the White schools, such as County, including being under-equipped in classroom supplies and sports equipment.

Evans told of an experience in a pharmacy in the 1950s. She described herself and her mother standing by the counter. She was waiting to get an ice cream cone. Evans wanted to sit on the stool, but it was against the law at the time. “In 1961, the Black community and White community leaders met; the lunch counters were quietly desegregated and other businesses followed in the next few years,” Evans said.

Evans explained that one day at Douglass Elementary school, her teacher told her to paint a picture. She painted a vase of flowers, and she entered into a county-wide contest and won a blue ribbon. “On this painting I had written words, ‘Segregation not only harms one physically, but injures one spiritually. It scars the soul. It is a system which forever stares the segregated in the face saying you are less than, you are not equal to,’” Evans said, quoting Martin Luther King Jr.

Evans explained how in 1963 her brother tried to sit in the White only downstairs section of the Tally Ho Theater instead of the upstairs balcony section; he was stopped and detained by the police. The teens in her neighborhood decided to protest in hopes of integrating the theater. She explained how the other kids decided not to protest because they were afraid, however, she and her brother stayed. Others later came to protest with them. “The next day teens from Purcellville and Leesburg joined our protest, teens began holding protests in front of the Tally Ho Movie Theater for about a week, and integration was achieved shortly thereafter.” Evans said.

She showed a picture she had painted of her and her friend sitting in the bottom section of the movie theater. “We were scared, I was scared. After integrating the theater, my friend and I sat downstairs. We saw the movie West Side Story. The seats were very comfortable, unlike the seats in the balcony. I enjoyed the movie but I felt scared because I felt out of place,” Evans said.

“The signs we were carrying are now in the archives at Thomas Balch Library,” Evans said. “They were found 45 years later. A lady had kept the signs in her attic and I donated them to the library.”

At one point, Black students were allowed to transfer to County and other LCPS schools. Evans painted a picture of her friend who had transferred to County. She explained how they didn’t get many new books at Douglass High School, and her friend had gotten his first new book. “After smelling his book, his teacher asked him what he was doing. ‘I’m smelling my book because I’ve never had a new book before,” Evans explained.

Evans showed a picture of a French class at County. She told of an experience of her brother. “He and his friend were the only Black students in his 12th grade French class. The White classmates sat many aisles over, four in fact. After class, a female student from England questioned why the White students sat so far away,” Evans said.

When integration finally came to Loudoun 14 years after Brown vs. Board of Education, Evans chose to stay at Douglass School. “Many of my friends who had protested that summer left Douglass High School to attend Loudoun Valley in Purcellville and Loudoun County in Leesburg in September 1963. I elected to stay at Douglass because I knew I couldn’t handle the trauma of entering a new environment, leaving a school where many of my friends were, and where I didn’t feel out of place. Many that did transfer shared conversations and did interviews that racism was present,” Evans said.

During a Q&A section at the end of Evans’ presentation, Laura Davies, a member of Gamma Sigma asked when Evans finally felt comfortable and included. “Not until I started sharing my story and this artwork,” Evans said. Evans was a teenager when these things took place, and now she is an older lady sharing her experiences.

People in attendance seemed inspired by the presentation. “I really liked the presentation, I felt it was very informative, and it was really nice to learn about the history of someone who was in Loudoun County during the time of segregation. It’s also nice for it to come from someone who experienced even the bad parts of it. I thought it was really nice,” member of the Black Student Union Ihanna Arceneaux said.

“You need to know your history, that’s all I’ve got to say. The good, the bad, the ugly,” Evans said.